Hong Wai

洪慧

Hong Wai et Pia Copper

|

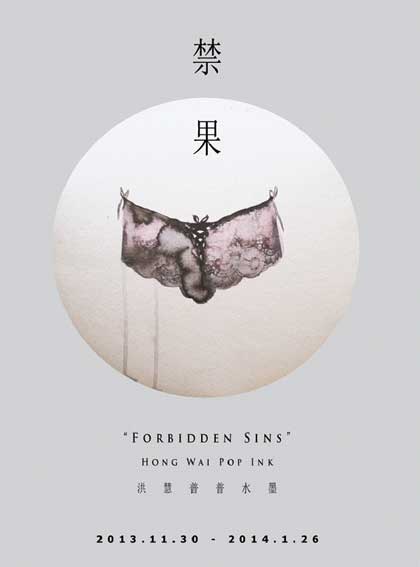

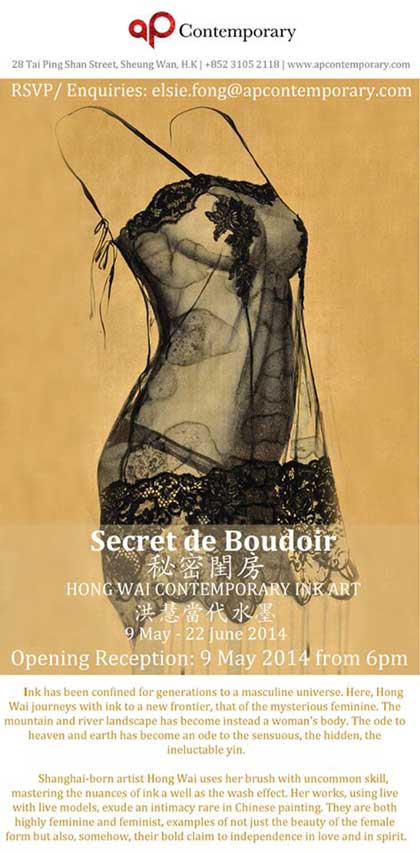

The boudoir is the anteroom in which a young woman quietly sits before a mirror, adorning and perfuming herself awaiting her love. The embodiment of that moment, the moment of embellishment, the moment of love is difficult to captureHong Wai’s paintings are in essence; about love. Her newest series of inks, Danielle, Anaïs, Elise, Doris, Emmanuelle, Louise, Vanessa, are like so many fox spirits or ling hu, the femme fatale in Chinese fairy tales, their unembodied apparitions in ink, evanescent and dreamlike. To paint the intimate clothing of women is to transgress a boundary in ink painting, almost as taboo as to paint a nude. For centuries, the traditional ink has been limited to landscape and calligraphy, the attributes of a Chinese gentleman, the Confucian literati or junshi. The reluctance of painting nudes comes perhaps as Francois Jullien, the French philosopher has suggested from the reluctance to paint subjects a such or figures; the Chinese gentleman or gentlewoman preferring to paint the world itself. The Buddhist and Taoist philosophy behind ink painting has always valued the suggestion more than the depiction, the essence more than the body, the spirit more than the incarnation. The ink “nudes” of Hong Wai (if we can call them nudes) are still in this regard very much in the literati tradition. They do not depict, but suggest. The body is still unpainted, only inferred. The head, figure, arms, hands of the subject are not apparent. The lingerie with its floating gauze, its lacy veils, gives the work movement. The body seems to take shape behind the layers of lace, which have been painted with a tiny brush. In contrast, the ink blotch effect or xuanran gives the effect of a landscape with clouds or pools of water; adding to the ethereal, floating atmosphere. The running ink, yunxing youmo, like threads of the embroidered garments, adds to this movement and evokes a body, one that might even be swirling, dancing or floating. The woman, like the fox spirit, seems alive. But she is indefinable, ineffable. Ink has been confined for generations to a masculine universe. Here, Hong Wai journeys with ink to a new frontier, that of the mysterious feminine. The mountain and river landscape has become instead a woman’s body. The ode to heaven and earth has become an ode to the sensuous, the hidden, the ineluctable yin. The pine branches and fern landscape of Vanessa, the roses and cloud landscape of Louise (which seems to be full of hidden, voluptuous bodies); the buds and blossoms of Anaïs leading to an avalanche of ink and water clouds, the cascades of leaves of Danielle’s opera-like kimono, all of these women seem in their own way to be landscapes. One can even glimpse a hidden dragon and cloud motif in Elise, somehow indefinable, yet very ancient, extremely Oriental. It reminds me ever so slightly of Pan Yuliang, an earlier 20th-century woman painter of nudes who lived in Paris. Pan rarely painted her “nudes” without clothing, portraying an open kimono, or a throw over a chaise longue which she inevitably decorated with flowers, leaves or other landscape motifs. Her nudes almost always appeared in their own secret gardens, their flesh complimented by the richness of the background or their adornment. Hong Wai’s ink creations are also their own jardin secrets, replete with sensuality. In the Tang dynasty, courtesans such as Yu Xuanji and Xue Tao employed all charms to entice their lovers. Gold hairpins, jade ornaments, woven silk gauze garments, nothing was too precious to lure secret love. The courtesan powdered her face, darkened her eyebrows and painted them into moons, into the shape of moths or flower blossoms, and covered them in gold and feathers. They then composed poems to entice; verses to bewitch. These love poems, were subtle hints at seduction, and eventual trysts. The poetry often referred to clothing, the “silver hooks” hinting at their amorous alliances, their silken robes alluding to their femininity and seclusion; the robes hiding her innermost sentiments and shielding her from the harshness of the world. As Yu Xuanji wrote: Shamed

before the sun, I shade myself with my netted gauze silk sleeve; Perhaps Hong Wai’s works are part of a deeper love poem. For the details in her work, the lace, she uses the same brush as was often used for writing: a tiny, intricate wolf brush, which could equally have been used for writing poems or love letters. |

||

|

© Pia Camilla Copper Paris, April 2014 |

||

Contact

All rights reserved

© chinesenewart Paris Mentions légales ![]()